REUTERS/Alexander Demianchuk

In the past, I have spoken about the possibility of a tsunami of change within the legal industry. It is something I have been carefully watching for several years and things now seem to be rapidly accelerating.

During a recent webinar discussion about legaltech startups, Professor Richard Susskind mentioned that several years ago there were a few hundred start-ups in the legal space, now there are a few thousand. This phenomenon lends itself to be the catalyst for the idea of a legal platform. How does the industry integrate all these disparate companies and their applications and have them work together? Well, solutions have been developed and new ones are being formulated, but first we need to understand the concepts.

What is a platform?

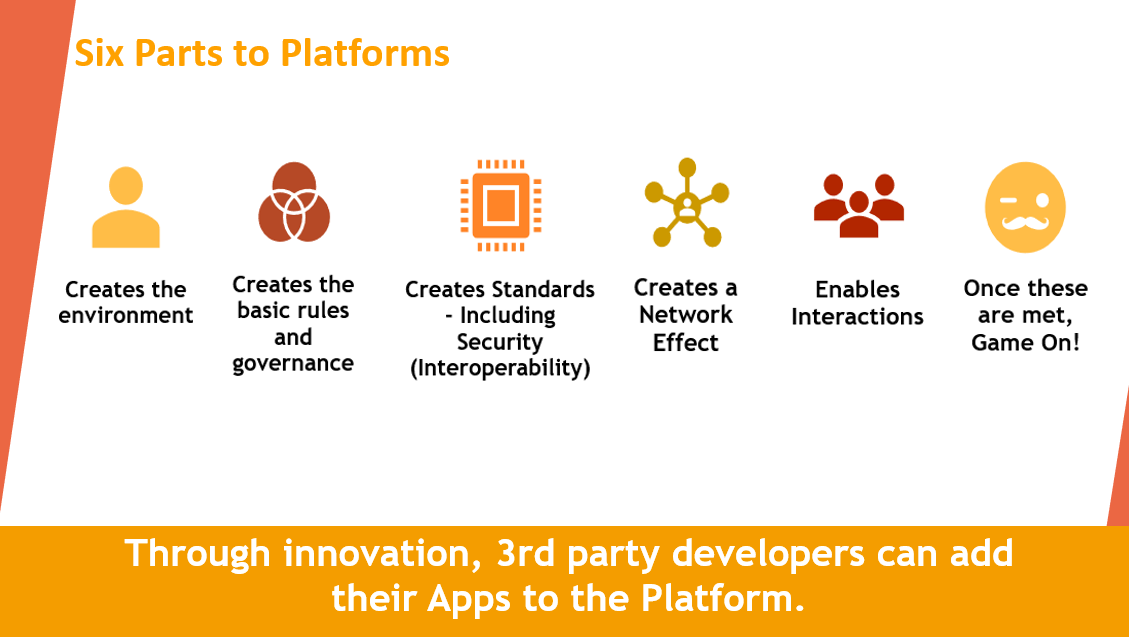

Platforms have existed for ages and in many forms. Simply put, platforms create an ecosystem or environment that allow people and business to participate if they abide by rules and meet standards. Ultimately this confluence creates a network effect for the community. For example, Apple created a platform in which anyone that uses a standard code set could programme their app and upload it to the Apple store for purchase. Many requirements are met before the app is available in the App Store, such as safety, performance, design, and legal commitments. The specificity is granular—an icon can only be a certain size, for example, and there is a 4,000-character limit for the app description.

Fundamentally, what this platform offers the consumer is a friendly, consistent, and reliable experience which is likely very secure. Both the developer knows what to expect, as the Apple platform dictates the rules, and the consumer has fair and reasonable expectations about their interaction when browsing, buying, and downloading an app on the platform.

One of the major benefits of a platform is interoperability. The concept that tools or apps can interact on the platform by exchanging information or leveraging other software, services, or even hardware. For example, if I grant permission, my bank app on my phone can interact with my phone’s camera to snap a picture of a check I want to deposit. My supermarket app can interact with my navigation system, alerting me to a 50 percent off deal on organic Ethiopian coffee as I pass the store. Information sharing, by permission, among interconnected applications creates efficiency and workflow, which as we will describe later, matters in the legal industry.

History of legal platforms

In 2018 the legal platform took flight. The concept or perhaps the term, while not new to most industries, was new to legal. Picture a world where hundreds, and now thousands of emerging companies exist around the globe. They all have their own code bases, built on a multitude of computer languages, and all vie to gain the attention of big and small law firms across both the business and practice of law. Many of these start-ups, competing against a host of known players in the legal space, have flooded the market like a new gold rush.

How does a law firm deal with a huge variety of applications, especially regarding installation, compliance, and security of each one of these apps?

The initial focus from the first platform created was on a concept in the software and application world called, ‘containerisation’. (Essentially, though, we are describing ‘standardisation’, with an emphasis on security.)

Law firms have been hit especially hard over the last five years, with hackers focused on exploiting intellectual property or other data behind law firm firewalls. The explosion of new applications on this myriad of codebases further complicates security. Ask any firm applications and IT specialist. When a new vendor plug-in for Microsoft Word is purchased by the firm, IT must test that plugin

- to see if it works on their version of Word;

- to test to see if it will interfere with 30 other plugins already imbedded in Word; and,

- to see if it interferes with any other applications at the firm. This is a massive pain point and source of cost for organizations.

Some firms I have met with have a six to twelve-month window to rollout a ‘single plugin’, primarily as a result of necessary testing.

Other companies offering legal platforms have tossed their hat into the ring, too. Some organisations across the legal landscape are uniquely positioned to not only create a platform, but hypothetically, to have hundreds of legal applications play on top of the platform from its inception. The surprising twist we are seeing transpire, which is consistent with all maturing industries, is a play to be inclusive of all competitors on a single instance. In this world of platforms, walled gardens can exist, but fully, truly open platforms are even more powerful. When organisations build a space where everyone can play, it tears down borders and enables customers to take full advantage.

Indeed, the perfect platform has no walls, and all players—companies from across the legal technology landscape—can put their applications on the platform, even the competitors of those that create the legal platform.

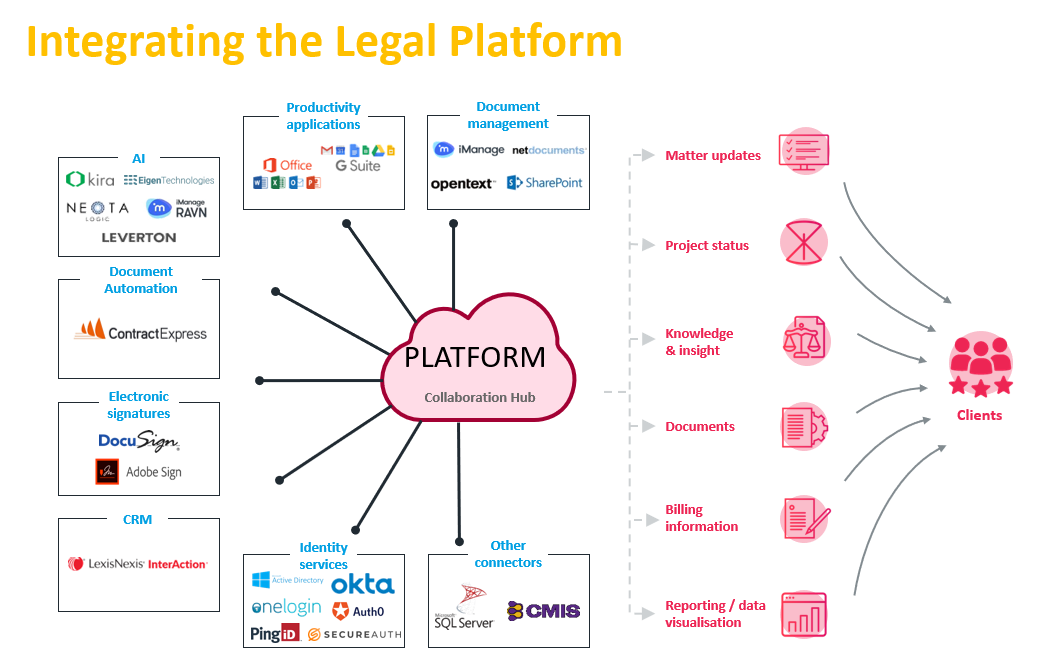

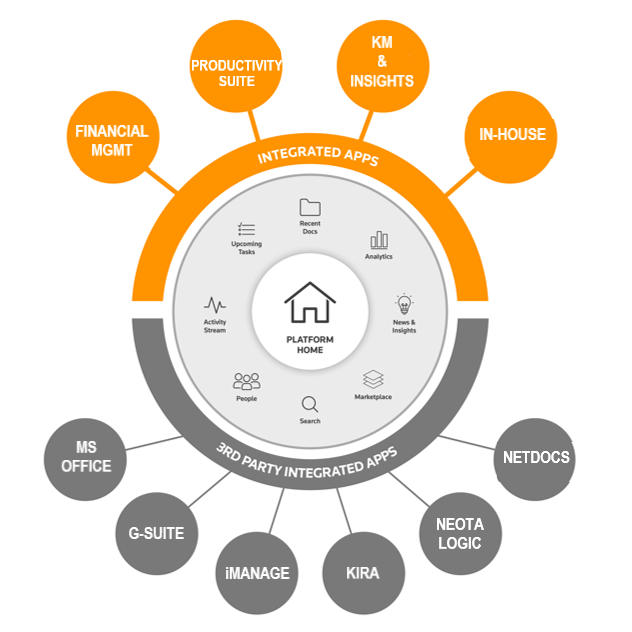

Once the legal platform is leveraged, you can see in the graphic above that tools can be integrated based on the organisational inclination. While most law firms tend to be Microsoft shops, there are a few global consulting agencies, such as the Big 4 accounting firms, that are using the G-Suite by Google.

In this new realm, all options are viable and permissible, allowing each organisation to choose its own adventure or mixture of products and services to best serve its clients or customers. While the legal platform in its relative infancy, there are currently several organisations already competing in this space.

The platform experience

To access a platform, users logs into their computer using their Active Directory credentials—normally, their Windows login information. Once verified, a user lands on a customised page that knows them professionally, for example, as an IP litigator partner, working on five cases for three clients. Then the platform gives users access to a bevy of resources. All this information is serviced up to them, including how many hours they have billed, current awareness about their clients, their latest court filings, and perhaps even a dashboard view into all of the ongoing engaged matters from their associates.

Or, does a partner need an app to review some new disclosure that just came to light? A lawyer can go to the Legal Platform App Store, see which approved eDisclosure applications have been approved and vetted by the firm, and immediately download it for use.

It is integrating activity streams, teams, search, documents, billing dashboards, and the interconnectivity of applications that can create workflow and enhance productivity and efficiency, all in a secure cloud-based platform.

In this next part of this series, we will examine application programming interfaces (APIs)—the cardiovascular system of the platform infrastructure.

Joseph founded wapUcom, LLP, consulting with companies in web and wireless development. As a side project DC WiFi was created to help create a web of open wireless WiFi access points across cities and educate people about wireless security. Currently Joseph is with Thomson Reuters Legal managing a team of Technologists for both the Large Law, Corporate, and Government divisions in the US. Joseph serves the top law firms in the world consulting on legal trends and customizing Thomson Reuters legal technology solutions for enhanced workflows. He graduated from Providence College with a BA in Economics and Sociology and holds a Masters in eCommerce and MBA from the University of Maryland, Global Campus.

By: Joseph Raczynski

By: Joseph Raczynski