With Premier League games being streamed online, Twitter spats ending up in the courts, and Deliveroo and Uber in the dock over workers’ rights – how is the law staying relevant?

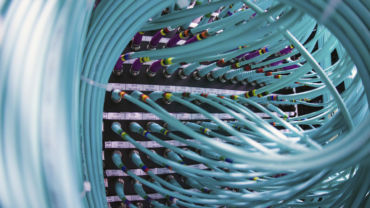

“The times,” as Bob Dylan sang, “they are a-changin’”. The internet, social media, smartphones, apps and peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms are transforming the way we communicate and do business, and the vast quantities of data generated are changing the way that companies interact with us. In a time of unprecedented disruption, the law needs to be at the forefront of change, helping to bring order to our messy digitised world.

“The law is playing a key role in meeting the challenges of this era of technological change,” says James Davies, Divisional Managing Partner at law firm Lewis Silkin. But, he admits, “it must continually play catch-up.”

The legal profession is not immune from the impact of technological change, says Davies, and is facing challenges from artificial intelligence, which could take work away from lawyers.

Richard Moorhead, Professor of Law and Professional Ethics at University College London, suggests that despite some developments to drive efficiency, innovation has been very modest. “Law is not having a ‘Kodak moment’. Not yet – and maybe never,” he says. Instead, law is wrangling with the changing landscape around privacy, copyright law and employment rights. But is it succeeding?

Jim Leason, Vice President of Market Development and Strategy for the UK and Ireland at Thomson Reuters, believes that the law has generally applied current principles to new areas, rather than develop new legal frameworks. This has worked so far, with judges expanding common law to fill in legislative gaps, he says. Whether this approach is sustainable remains to be seen.

Smartphones and the gig economy

The cases taken against taxi-hailing company Uber and food delivery firm Deliveroo have made headlines, as their drivers and riders have sought to be treated as employees – rather than as self-employed – and afforded the same employment rights.

In the Uber case, brought by the GMB union, the London Employment Tribunal ruled that its drivers can be classed as workers, and are entitled to holiday pay, paid rest breaks and the national minimum wage. The company – already fighting to continue its business in London – recently lost its challenge to that ruling in the Court of Appeal, but has indicated it will take the case to the Supreme Court.

Conversely, in the case against Deliveroo by the Independent Workers Union, the Central Arbitration Committee has ruled that its riders are self-employed because they can ask a substitute to take their place on a job. Its riders are therefore not entitled to basic employment rights.

Nigel Mackay, associate in the employment team at Leigh Day, which represented the Deliveroo riders, says that the power of technology to the gig economy is a “big game-changer”, yet both cases deal with “old-fashioned problems regarding employment status”. The legal principles regarding worker status, he says, are good, but he would like to see measures to enforce decisions and punitive damages awarded against companies that wrongly seek to deny their workers rights by falsely classifying them as self-employed.

The issue has become a political hot potato as the number of gig economy workers grows. A draft bill recently published by the Work and Pensions Select Committee, and the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee proposes a presumption of ‘worker’ status and corresponding rights, putting the onus on companies to prove self-employed status. It also seeks to introduce the punitive damages that Mackay would like to see.

The messy legal landscape of the internet

The legal issues that the law must seek to clarify around the internet, social media and global connectivity are immense, spanning defamation, data protection and copyright, to name a few. Davies of Lewis Silkin reckons national laws are sometimes ‘ill equipped’ to cope.

Various decisions of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) have sought to police the online marketplace and clarify what amounts to copyright infringement. Earlier this year, in The Pirate Bay case, the court ruled that the site, which allows users to share links to download films, TV shows and other content, could be liable for copyright infringement.

In 2014, the Court said that internet browsing does not infringe copyright, and that hyperlinking to a copyright work that is freely available on a website does not infringe copyright. It later ruled that hyperlinking to content posted on the internet without the copyright owner’s consent could infringe copyright in certain cases, in particular where the links were provided for the pursuit of financial gain.

UK Courts have grappled with similar cases. In Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation and others v Newzbin Ltd, the High Court held that a company that ran a members-only website, effectively operating a P2P sharing network collating files and enabling searches of posted content, had infringed copyright. The Court ordered BT, the internet service provider (ISP), to take measures to block access to the Newzbin website.

Last year, the Court of Appeal took a step forward in upholding the rights of brand owners, backing the High Court’s decision that blocking injunctions applied to trademarks as well as copyright works. It ordered that ISPs were required to prevent customers from using their services to access trademark infringing content. Earlier this year, the High Court ordered six major ISPs to block access to specific server IP addresses that were delivering live pirated streams of Premier League football matches. What’s clear is that nuance is key in each case.

In relation to data protection, the ECJ’s ‘right to be forgotten’ ruling enabled individuals to request the removal of search results about them where it infringed their privacy.

The law has had mixed results in addressing defamation and the internet, although commentator Katie Hopkins was ordered to pay damages of £24,000 to Jack Monroe, a food blogger who she had defamed on Twitter.

Social media is also spawning employment law cases, Mackay notes, as employees can find themselves in hot water over information and pictures they share online.

What does the future hold?

Websites such as Google and Facebook, which hold vast amounts of personal data about their users, are facing challenges over what they do with that information. Austrian privacy campaigner Max Schrems has been fighting a lengthy battle with Facebook over privacy violations, seeking to stop the site from transferring personal data out of the EU. Facebook is also tangled up in the high profile Cambridge Analytica data breach scandal.

Recently, an advocate general of the ECJ gave Schrems the green light to sue the social media giant, but only on his own behalf, rather than bringing the class action he had sought to take.

Looking ahead, says Leason, the law will have to address a plethora of issues, ranging from liability for accidents caused by driverless cars and issues surrounding the use of drones, as well as continuing to grapple with the evolving use cases for blockchain and cryptocurrencies, and the transnational issues that they will bring.